“This is where our padre, David Cooper, was so marvellous. He took each section (nine men), the smallest fighting unit in the battalion, sat down in front of them and said, ‘Look, when we go on this battlefield, it’s going to be bloody awful. Now, I don’t know about you, but I’ll tell you how I’m going to feel.’

This has got to be one of the most fundamental questions any team leader wants to know the answer to. So much of what teams do is based around taking action. For any team to succeed, its members must make that decision to move from inertia to motion, to choose to do things they may deem hard, or dangerous, or exciting, or beneficial to their own desires. Whatever the reason, the leader needs to know how to persuade, cajole, convince or simply instruct his or her subordinates to act.

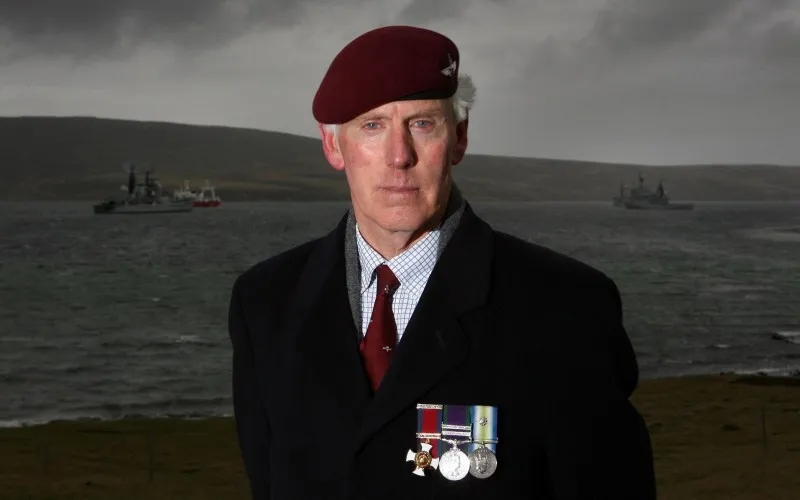

What got me thinking about this was a recent article I read by Lieutenant Colonel Chris Keeble DSO who served with the Parachute Regiment of the British Army during the 1982 Falkland War.

In it, he says:

“The whole point of war is to apply violence to break the enemy’s will, not simply to destroy his weapons or cities, but to undermine his will to fight for what he believes in. How do you reinforce that will in a body of people who have never been to war?”

I will come back to his answer later, but for now, I can’t think of many situations where the stakes are higher for the leader of a team than in the theatre of war – the need to be able to convince the members of that team to act in service of the team’s goals that could result in their death. (This is one of the many reasons why we look to the military for examples and lessons on how to ‘do’ teamwork – the extreme nature of their decision making and actions gives us valuable lessons we lucky people who have far safer jobs can learn from).

I am constantly fascinated by this factor of military leadership, the need for leaders to instruct their soldiers to risk life and limb. I remember reading a book called ‘Once a Warrior King’ by Lieutenant David Donovan about his experiences fighting for the US Special Forces in Vietnam. He tells the story of a particularly fierce firefight he was leading troops in, when they were pinned down against the bank of a rice paddy field, and his troops where extremely reluctant to continue the fight – preferring, quite understandably, to keep their heads down and preserve their own lives.

He had reached that point that every office dreads – no amount of instruction, persuasion or shouting was having any effect – the men simply would not budge. What do you do now?

And what do you do, when you reach an impasse, a stubborn point blank refusal to do what is needed? Donovan knew that he had to get the men to move forward – to sit still meant destruction. But how?

Suddenly, he remembered a lecture he had received from a World War II veteran commander when he was in training at the US military academy, West Point. One of his fellow students had asked this grizzled old soldier what do you do if your men won’t go forward? And his response was simple – you stand up. Stand up and walk up and down the line, and tell the men to follow you. It may go completely against every fibre of your being to put yourself in such obvious harm’s way, but this is your job as a leader, this is why you have been chosen to lead, and this is what is expected of you. Stand up. Walk. Talk. And show the way.

At that moment of crisis, these words leapt into Donovan’s consciousness. A calm clarity came over him, as he realised this is what he must do. And so, he stood up. Despite the clamouring of the men around him to lie down, and the hands grabbing at his clothes trying to pull him back down into the dirt, he remained upright and quite deliberately walked up and down the line, giving the men calm but firm instruction to stand up and fight through the paddy field towards the enemy position. The moment he stood, he could hear and literally feel the eruption of enemy fire as their soldiers doubled their efforts to hit such an obvious target. Despite the fear, he kept going. And one by one, his men stood up. Eventually, the whole platoon was moving forward and the day was won. Yes, their were casualties, but Donovan and the majority of his men survived – something that would not have happened if they had remained inert, clinging in fear to the side of that paddy field.

This is an example of a very visceral, in the moment response to the question of convincing a team to act. Highly charged, adrenalin fuelled and without time to think. In contrast, Chris Keeble had plenty of time to consider this question, as the British forces made the long journey through the Atlantic towards the Falkland Islands. How were they to convince young, raw troops to go to war for the first time, and potentially die in the service of their country? Here’s what he did:

Cooper attempted to penetrate that macho façade soldiers build around themselves in order to reinforce their own inner resistance to fear. By voicing their own fears to them, he got them to talk about how they would actually cope with the trauma of war. Being a padre, and to some extent apart from the military structure, he gave them the opportunity to share their emotions with each other, developing a ‘spiritual’ bond within the sections, which is essential if people are going to work successfully together – and, for the 2 Para team, to die for each other”.

So what do we learn about convincing people to act from these two examples? There are a few things that might apply to your situation to think about.

Establish Authority, Trust & Respect for your Leadership from your Team

As a leader you need to have the authority, trust and credibility of command. Without this, you are dead in the water. How do you establish this? Well, this is really all about what has been called ‘The Mask of Command’ by historian John Keegan in the book of that title, and I have written in greater depth about leadership in this previous post. Suffice to say that Keeble and Donovan both had the respect and trust of their men – otherwise they would not have gotten off the start line, let alone been able to persuade them to fight. Be a good leader, and people will follow.

Instil Purpose

Teams need to know why they are doing what they are doing. You may create and communicate this, or let them discover and craft this for themselves. Purpose is everything in motivating teams. Giving people a strong, compelling reason why they would choose to take action, especially at great personal risk or which requires supreme physical or mental effort, is mandatory to successful teamwork. Soldiers are tasked with lofty goals of defending the nation, or defeating evil, but mostly you will find that they fight for the person next to them. This is why I say as well as creating your team’s purpose from above and communicating it downwards, don’t underestimate the power of letting the team craft their own purpose. The results can be surprising and incredibly meaningful.

Be Open About the Grim Truths

Keeble asked the padre to go round and discuss the possibility of death with all his soldiers. He didn’t hold back, and put everything on the table for discussion about what might happen. Open, honest communication around the grim realities and possible pitfalls or choke points of a team’s existence and story keeps fear at bay. Shining a light into the dark corners that everyone knows are there, discussing the elephant in the room, is a great way of assuaging fear. I have always been a believer in openness, truth and honesty with my team, no matter what – you will find that people far prefer to know everything rather than being kept in the dark. Darkness is where rumour, exaggeration and gossip live – poison to teams.

Be Vulnerable

The padre, David Cooper, sat with the men and shared his true feelings with them. He was prepared to admit fears, possibly that he didn’t have all the answers and didn’t know what was actually going to happen – but that simply this is how he felt. Leaders who are prepared to admit these kind of things and appear vulnerable will endear them to the team, instil compassion and create potentially huge loyalty – a fabulous commodity for any leader and team. It takes guts, it might be risky, but vulnerability can be your greatest ally as a leader.

If/Then Thinking

Part of the padre’s mission will have been to ask questions like ‘what do we do if the guy next to me goes down’? or ‘how will I react if I am shot’? In team-speak, this is a bona fide tactic called ‘if/then thinking. If this happens, then we do that. Good teams try to predict possible events, anticipate the unexpected and action plan around what to do if that happens. This is a great tool or practice that any team can easily adopt themselves to minimise inertia, indecision and mistakes at crucial times.

Give Clear Direction and Instruction

When David Donovan was walking up and down the line, despite the heat of battle, he gave clear, concise direction to his troops. Sometimes, leaders have to be very direct to their charges. Yes, sometimes you have the time and ability to have a discussion around goals and work tactfully with people to persuade them to do things – but not when the pressure is on and time is of the essence. Luckily for most of us, this doesn’t mean when bullets are whizzing and cracking past our heads in a life threatening firefight, but the principle will apply at some points for a lot of leaders. Be ready at the right time to be firm, confident and give complete and direct instructions quickly to your team – instructions that illicit a clear response, and that don’t meet with questions.

Don’t Run

A crucial aspect of Donovan’s actions was that he walked up and down the line, giving instructions to his men. He did not run. As a leader, you are constantly on show, under the scrutiny of your team, even if you don’t think so. Trust me, they are always watching. Teams look to their leaders for guidance and example, and you as the leader are running around like a headless chicken, your panic will infect the team like a virus. If however, the you are displaying a calm and deliberate confidence in the face of adversity, this will relieve and inspire the team, and diffuse panic and indecision. As a leader, never run – literally or figuratively.

HOW TO GET IN TOUCH

Call me on +971 (0)50 559 5711 or send me a message